Table of Contents

Overview

Shock is a life-threatening clinical syndrome characterized by inadequate perfusion of vital organs such as the heart, brain, and kidneys, leading to cellular and metabolic dysfunction. Early recognition and targeted intervention are essential to reverse shock and prevent irreversible organ failure. This article outlines the causes, pathophysiology, stages, and emergency management of shock, providing a high-yield reference for final-year medical students.

Definition

- A state of profound circulatory and metabolic dysfunction due to inadequate tissue perfusion and oxygen delivery

- EXAM tip: “Inadequate perfusion of vital organs (heart, brain, kidneys)”

Aetiology

Hypovolaemic

- Due to loss of blood or fluids:

- Severe dehydration: Vomiting, diarrhoea, diabetic ketoacidosis, burns

- Haemorrhage: Trauma, GI bleeding, postpartum haemorrhage

Cardiogenic

- Due to primary pump failure (heart unable to maintain cardiac output):

- Acute myocardial infarction

- Valvular disease

- Cardiomyopathies

- Myocarditis

Distributive

- Loss of vascular tone → inappropriate distribution of blood volume

- Septic shock

- Anaphylactic shock

- Neurogenic shock

Obstructive

- Due to physical obstruction of blood flow:

Pathophysiology & Compensatory Mechanisms

- Cardiac reserve: Maximum % cardiac output can increase above baseline (normally 300–400%)

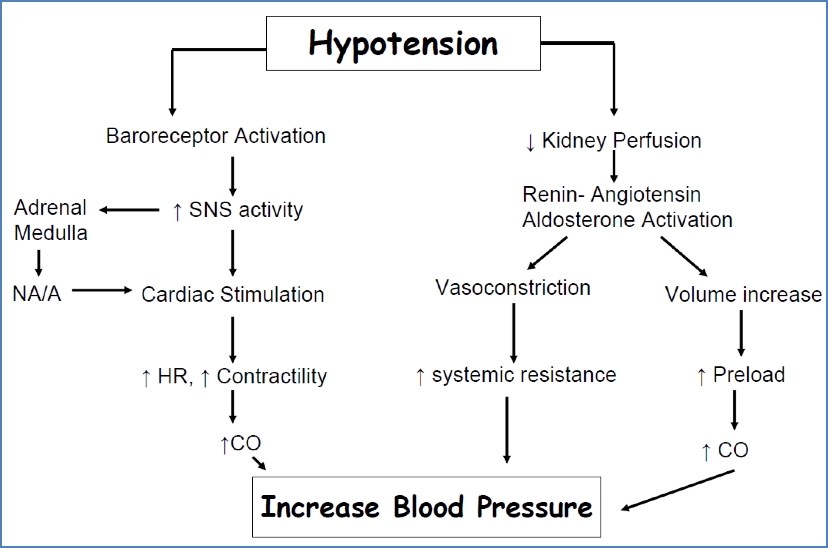

- Immediate response:

- ↓BP sensed by baroreceptors → ↑Sympathetic tone → ↑HR, ↑contractility, vasoconstriction

- Delayed renal response:

- Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system → Vasoconstriction and sodium/fluid retention

- Vasopressin (ADH) → ↓urine output → ↑blood volume

- Erythropoietin → ↑RBC production

Stages

1. Non-Progressive (Compensated)

- Perfusion maintained by compensatory mechanisms

- Symptoms:

- Hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnoea

- Oliguria

- Clammy skin, chills

- Restlessness, altered mental status

- Urticaria or wheeze if anaphylaxis

2. Progressive (Decompensated)

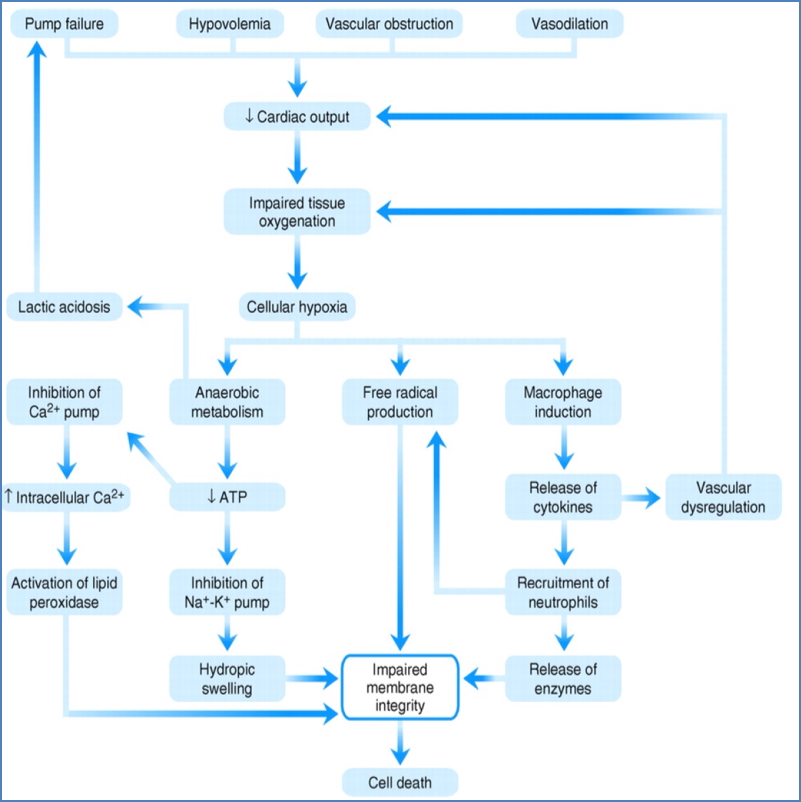

- Vicious cycle of cardiovascular deterioration

- Tissue perfusion continues to decline → end-organ ischaemia

- Pathology:

- Myocardial hypoxia → cardiac depression

- Brain hypoxia → vasomotor failure

- Capillary leak, increased viscosity → “sludging” of blood

- Symptoms:

- Worsening mental status

- Bradycardia (late stage), dyspnoea

- Cold, mottled skin

- Metabolic acidosis

- Requires immediate treatment or is fatal

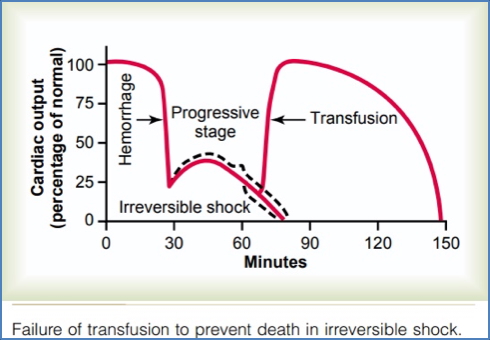

3. Irreversible Stage

- End-organ damage beyond recovery

- Treatment ineffective despite resuscitation

- Symptoms:

- Renal failure, myocardial failure

- Coma, severe hypotension

- Worsening lactic acidosis

- Ischaemic cell death

Shock-Induced Cell Death – Self-Perpetuating Cascade

Management

General Principles

- Recognise the cause → reverse it

- FLUID REPLACEMENT is first-line in most shock types

Specific Management

- Hypovolaemic shock:

- IV fluids (normal saline), stop fluid loss

- Septic shock:

- Blood cultures, broad-spectrum IV antibiotics

- Fluids + vasopressors (e.g. norepinephrine)

- Anaphylactic shock:

- ABCs, IM/IV adrenaline

- Steroids and antihistamines

- Cardiogenic shock:

- Inotropes (e.g. dobutamine), nitrates, PCI

- Treat underlying cardiac pathology

- Obstructive causes:

- PE → Thrombolysis (tPA), embolectomy

- Tamponade → Pericardiocentesis

- Pneumothorax → Needle decompression

Fluid Therapy

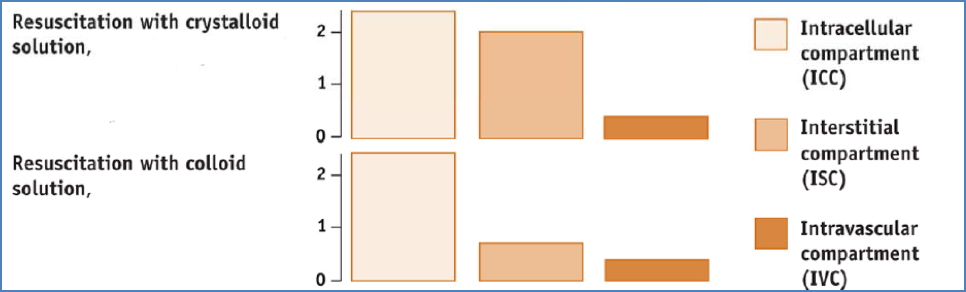

Crystalloid vs Colloid Solutions

- Crystalloids:

- Low osmotic pressure, cheaper, more widely used

- 25% remains intravascular

- Includes:

- Normal saline (isotonic; most commonly used)

- Dextrose (not used for resuscitation; good for hypoglycaemia)

- Lactated Ringer’s / Hartmann’s (electrolyte-balanced; buffers acidosis)

- Colloids:

- Higher intravascular retention (all fluid stays in circulation)

- Includes:

- Albumin: Used in sepsis, burns, liver failure

- Polygeline (Haemaccel): Useful for GI fluid losses

- Blood products:

- Whole blood: For massive haemorrhage

- Packed RBCs: To increase O2 delivery

- Plasma: For volume + clotting factors

Fluid Resuscitation Principles

- Bolus: Estimate and replace acute loss (e.g. 2L)

- Maintenance – 4:2:1 Rule:

- 4 mL/kg/hr (first 10kg)

- 2 mL/kg/hr (next 10kg)

- 1 mL/kg/hr thereafter

- Crystalloids vs Colloids:

- Colloids more effective in pressure support

- Blood is best for restoring oxygen-carrying capacity

- Dextrose unsuitable for resuscitation

Summary

Shock is a state of inadequate tissue perfusion that leads to cellular dysfunction and, if untreated, multiorgan failure. Understanding the types and stages of shock allows clinicians to rapidly identify the underlying cause and apply targeted management. First-line therapy typically involves fluid resuscitation, with specific interventions depending on the shock subtype. For a broader context, see our Cardiovascular Overview page.