Table of Contents

Overview – Grief & Loss

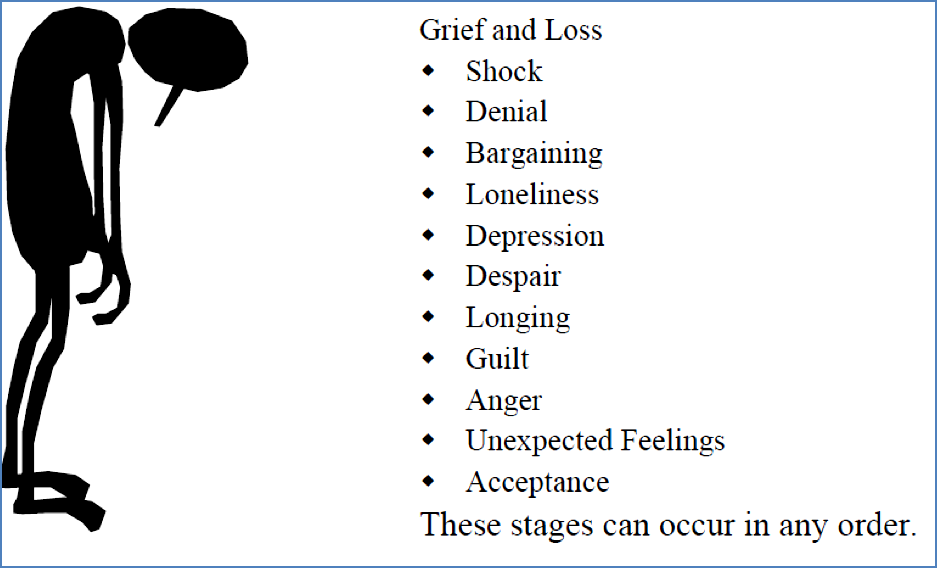

Grief and loss are universal human experiences shaped by cultural, social, psychological, and biological factors. While grieving is a natural response to loss, its manifestations vary widely across individuals. This article explores the dimensions of grief, models of coping, psychological adjustment, and indicators for formal support. A practical understanding of grief is vital for clinical care, especially in mental health, palliative care, and general practice.

Definition

Grief is a multidimensional emotional response to the loss of a loved one, role, or identity. It is influenced by:

- Culture

- Age

- Gender

- Physical and mental health

Every person grieves differently, and there is no “correct” way to grieve.

Dimensions and Manifestations of Grief

Physical

- Somatic complaints: chest pain, stomach aches, headaches

- Sleep disturbance

- Changes in appetite and weight

- Fatigue

- Breathlessness

Emotional

- Sadness, numbness, fear

- Guilt and self-blame

- Anxiety, crying, helplessness

- Anger or even relief (e.g. after prolonged illness)

- Loneliness and yearning

Cognitive

- Decreased concentration and memory

- Nightmares or preoccupation with the deceased

- Magical thinking (irrational beliefs)

- Confusion or disbelief

- Thoughts of death or dying

Behavioural

- Withdrawal

- Regressive or aggressive behaviour

- Obsessive activity

- Risk-taking or self-destructive behaviour

Spiritual

- Increased reliance on spiritual beliefs

- Loss or questioning of spiritual faith

Secondary Stressors

Loss often triggers additional sources of distress:

- Financial strain

- Legal complications

- Single parenting

- Identity loss (e.g. “Who am I if I’m no longer a spouse?”)

Models of Grief

Freud’s Psychoanalytic Model

- Early model proposing mourning as psychological detachment from the lost object

The Dual Process Model (DPM)

- Modern, flexible model incorporating two key domains:

| Loss-Oriented (Early) | Restoration-Oriented (Later) |

|---|---|

| Grief work | Life change adjustment |

| Intrusion of grief | Doing new things |

| Denial or avoidance of restoration | Distraction from grief |

- Individuals oscillate between these two processes to eventually adapt to their new reality

Adjustment and Resilience

Adjustment

- Grief is natural and expected

- Most people cope through informal supports (e.g. friends, family)

- Formal support (e.g. counselling or medication) is not always required

Resilience

- Most common grief trajectory

- Includes a range of pathways:

- Recovery with some symptoms

- Chronic grief (less common)

- Delayed grief is rare

- Pragmatic coping styles often show:

- Reduced expression of intense negative emotion

- Effective emotional regulation

Protective Factors

- Strong social network

- Capacity for positive emotion

- Flexible and problem-focused coping

When to Seek Support

Grief does not always require intervention. Support is recommended when:

- The individual asks for help

- Maladaptive coping is evident (e.g. substance misuse, compulsivity)

- There are thoughts of suicide or self-harm

- The person feels alone or helpless

Supporting the Bereaved

What they need from you:

- Presence and empathy

- Space to talk or cry

- Listening without judgment

- Occasionally, short-term pharmacological support (e.g. low-dose benzodiazepines for insomnia or acute anxiety) may be appropriate under clinical supervision

Summary – Grief & Loss

Grief and loss impact individuals physically, emotionally, cognitively, behaviourally, and spiritually. Though highly individualised, most people adjust without formal intervention. Understanding common trajectories, such as the Dual Process Model, helps clinicians identify when support is needed. For a broader context, see our Psychiatry & Mental Health Overview page.